In just under a month, it has become apparent that the war in Ukraine will hammer the Lebanese people and economy. With oil prices hovering at around US$100-120 per barrel and completely cut off from its main wheat suppliers Russia and Ukraine, the ruling class now faces its first global food price crisis since 2008.

Back then, they were not as worried: Lebanon was a safe haven for foreign currency fleeing the Global Financial Crisis, with billions upon billions of foreign currency flying into the coffers of Lebanon’s commercial banks. In the years that followed, food, housing, and basic goods became unaffordable to more and more ordinary citizens—but those with bank accounts (around half the population) still had their income-generating interest rates. By and large, the Lebanese believed the financial sector was linchpin of the ‘Lebanese miracle,’ touted as gospel by a klepto-banking elite. Sadly, gifts from god are in short supply these days.

This time around, Lebanese elites have nowhere to hide. For weeks, public debate swirled over whether to demolish the grain silo in Beirut’s port, before moving to where to import wheat from and then store it. In the coming months, everyone in Lebanon—residents, refugees, migrant workers, and foreigners—will face an even starker reality. Their purchasing power will shrink due to knock-on effects from higher oil prices and supply shocks to basic goods and services.

Stopgap measures will buy the ruling class time. The long-awaited ration card programme, denominated in US Dollars, provides some respite to some the most vulnerable—even if the programme is funded through a loan that will only add to the country’s already unsustainable public debt. Substitution of wheat for other staples can help, but even food imports like rice have witnessed price increases of some 20% in the past year, not least because of COVID-19 supply chain issues.

As long as the global food and energy crisis continues, Lebanese households – which rely overwhelmingly on imported products – will start skipping meals, eating less, losing nutrients, and falling ill. Hospitals have already stated that, by May, all patients must make payments in foreign currency, effectively removing all medical cover for subscribers to the state’s National Social Security Fund (around 25% of the population) and other insurance schemes.

This widespread deprivation represents a nightmare scenario for the ruling class on the cusp of parliamentary elections, which are scheduled for May 2022. Once again, the only place for them to turn are country’s dwindling foreign currency reserves, which consist largely of ordinary depositor’s money (required reserves) and gold. With just a few weeks to go before the election, the ruling class will almost certainly continue to resort to this dangerous option, pushing Lebanon even closer to the brink. But there is another way.

However painful, an injection of capital by the IMF accompanied by reform is the obvious choice. Yet the Association of Banks in Lebanon are avoiding a deal, not only because it would force them to take on a fairer share of losses, but also because it would remake the banking sector of the future.

Despite what the klepto-banking elite claim, almost all banks will need to be rescued through a combination of debt write offs, bail-ins, and consolidation. The last measure is particularly worrying for the banks: it means books will have to be opened, and better-off banks will have to share ownership with worse-off banks.

That would mean banks founded on sectarianism and patronage systems—such as BBAC for Druze powerbrokers, and BankMed for the Sunnis—will have to accept shareholders and managers from other sects. Such an outcome would dilute, if not shatter, the financial pillars of sectarian patronage in the country. So don’t be surprised if IMF negotiations drag on for months, if not years.

For the opposition, which is vying for public representation in the next election—now is the time to strike. The upcoming food crisis must be used as ammunition to dilute support among even the most ardent supporters of the ruling class. The opposition must propose a real alternative, one which insists on a fair, transparent, and accountable solution to the financial crisis.

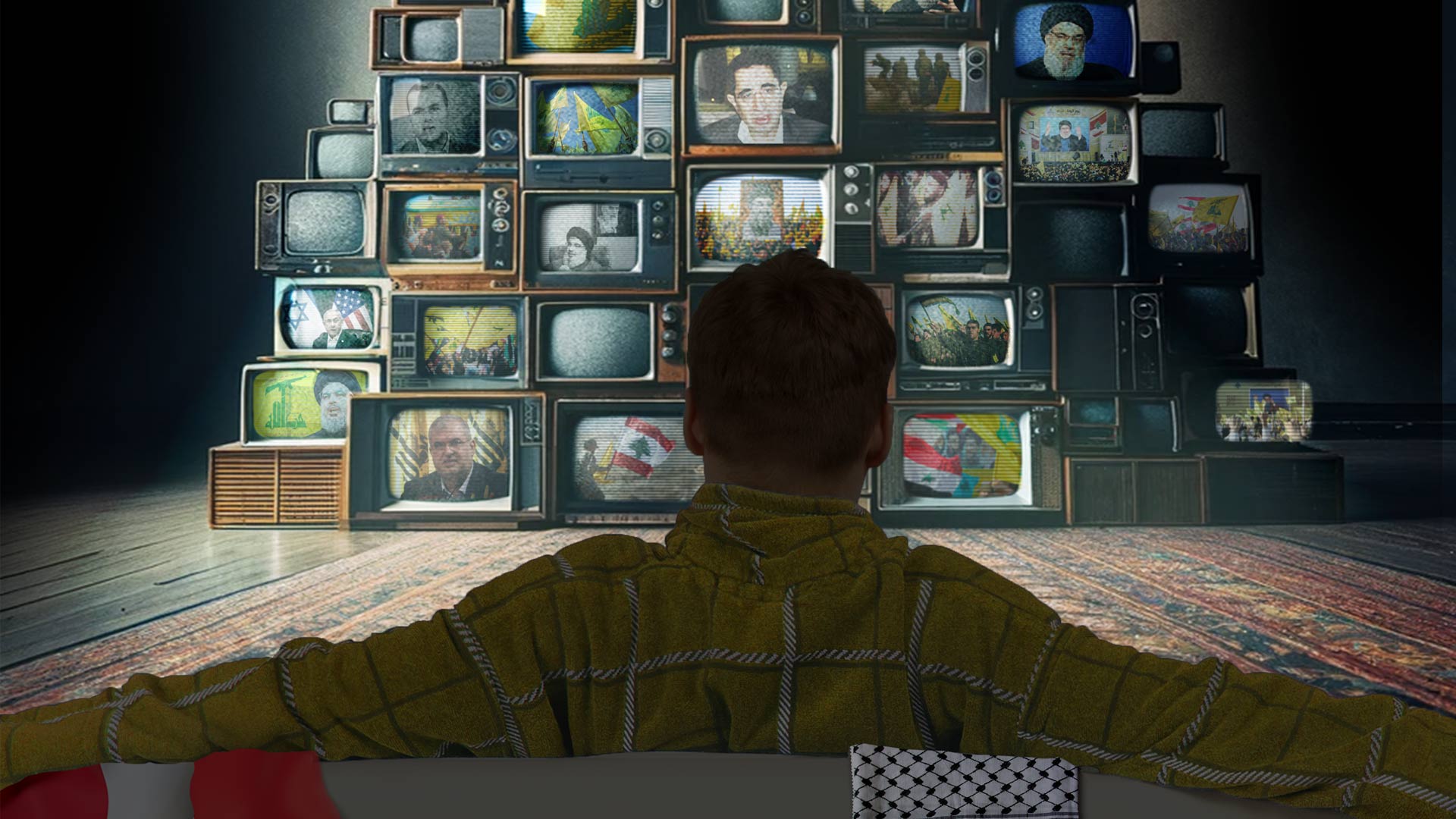

In doing so, opposition groups need to be serious about their financial reform plans, dealing first and foremost with peoples’ immediate needs. In parallel, the opposition must make clear that the sectarian rhetoric gushing forth during election season is nothing more than an attempt to prolong the ruling class’ choke-hold on what’s left of Lebanon’s financial system.